by Jeff Fraser, RYERSONIAN STAFF

by Jeff Fraser, RYERSONIAN STAFF

Published on 10/15/2012

I have debt – a lot of it. Some nights I wake up in a cold sweat from nightmares about default and bankruptcy. Like many students, I dread the six-month anniversary of my graduation, when I’ll have to start repaying my loans and begin the long slog towards financial freedom.

Those of us with debt will be living with it for a long time. But what does that mean? How will my debt affect my future, and what can I do about it? Should I be cutting down on lattes, or planning to flee to Albania?

I decided to do what I should have done seven years ago when I first headed off to university: ask for financial advice.

And what did I discover? Debt is not as scary as most of us think. It’s all about the way you deal with it.

“Debt is almost like a force of nature – it can roll over you, and have a lot of negative impact on you,” said Jason Pereira, an independent financial consultant who helps clients with insurance, tax planning and debt management.

“It’s always going to be there until you pay it off, and you can’t count on everything else

being perfect all the time,” he said. “If you lose your job, if you’re without income for a couple of months because of an accident, even with insurance protection – you’re in a lot of trouble.”

Pereira said that graduates earning low to modest income should try to pay down their debt as soon as they can after graduation. For me, that’s about $55,000, split between OSAP and a Scotiabank student line of credit.

“Fifty-thousand dollars seems like a world of debt, but if you come out of school earning a decent income, it’s totally doable,” he said. “If you’re coming out earning a weak or modest income, it’s going to be harder.”

When I asked what “decent income” meant, he said that a full-time job is probably enough and a part-time job may even be adequate. I won’t need to be making $60,000 to repay my loans, but while I’m in repayment, it will be much harder to save for a marriage, car, or home.

“There’s no magic to this,” Pereira said. “You either save up the money to pay for what you need, or you don’t and you can’t afford it. Debt is going to curtail your ability to do that.”

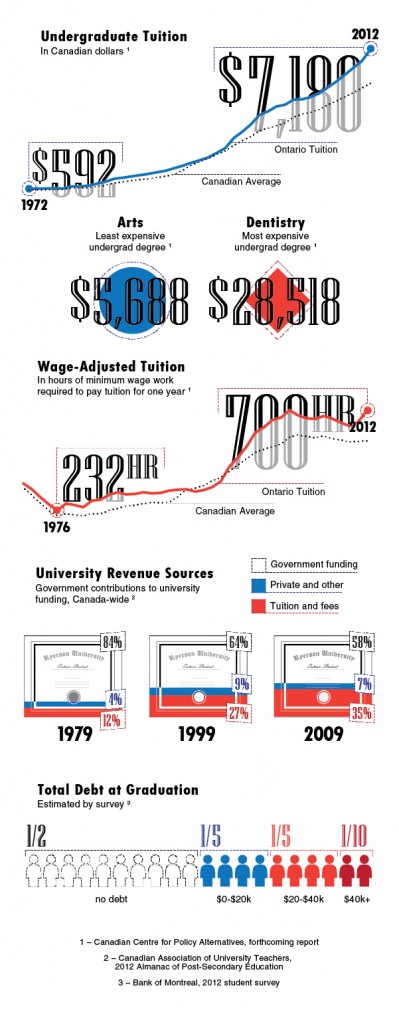

In 2005, Statistics Canada calculated the average student debt as $18,800. At $55,000, my debt load is nearly triple that. A survey of 1,000 Canadian post-secondary students released earlier this month by the Bank of Montreal found that 28 per cent of students expect to graduate with more than $20,000 in debt. About 10 per cent expect to graduate owing $40,000 or more while 51 per cent of students expect to graduate without any debt.

I was one of the students who underestimated their debt. When it came to financial responsibility, I followed the rules – I didn’t use a credit card, I kept my discretionary spending low and I never went on vacations. I took five years to earn my bachelor’s degree because I worked full time through 2010 and 2011, and with my full-ride scholarship at Ryerson, my master’s is virtually debt-neutral.

It sounds like I should be in decent shape, but I’m sitting in the hole for the price of a new Audi A6.

What the hell went wrong?

With the benefit of hindsight, I know I went to school with mistaken beliefs about how my education was supposed to go. I believed, for instance, that I should be able to live away from home, because it was an essential component of the traditional college experience.

But my first year in residence cost $1,250 a month, including board. For the next three years, I was paying $400-$600 a month plus utilities and groceries – and feeling guilty every time I bought a pitcher of beer.

I believed I would be able to work off my debt while I was at school because that’s what my dad did. I didn’t realize that average tuition in Ontario was $1,176 per year when he graduated in 1985. Today it’s $7,180.

In case there are any doubts about the worth of a dime in 1985 versus 2012: assuming my dad worked 20 hours a week at the minimum wage of his day and devoted 30 per cent of his income to paying for school, numbers at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives show that he could have paid for his degree in four years and graduated without debt. The same arrangement for me, at today’s minimum wage, would take about nine years.

Today, going to university depends on other people’s money, whether it’s a government handout, a merit-based scholarship, or your parents paying for the roof over your head. It’s not just about budgeting anymore – students like me have to come to terms with a new college experience, which involves debt the same way buying a house involves a mortgage.

The maximum repayment period that OSAP offers is 15 years. With that option, repaying my debt will cost about $430 per month. If I can find work as a journalist in Ontario, Statistics Canada says I can expect to make a starting salary between $18,000 and $35,000, which means paying down my debt will eat up somewhere between 15 and 30 per cent of my income.

On the low end, that leaves around $1,200 a month for rent and living expenses after I’ve made my payments. I’ll still be living in a hole in the wall, but like Pereira said, it really won’t be the end of the world.

Jason Abbott, another independent adviser, said “There’s an old saying among financial planners: ‘Not all debt is created equal.’” Students need a paradigm shift on school debt. He said we need to see it as a natural, even healthy, aspect of our financial lives, rather than a terror to keep us up at night.

Of students who responded to the BMO survey, 27 per cent said their biggest stress was debt – more than those who picked finding a job (22 per cent) or getting good marks (20 per cent). But Abbott said student debt shouldn’t be that scary.

“Ask any student out there whose parents have a mortgage: Do they fret on a day-to-day basis that they owe two, four, six hundred thousand dollars to a bank?” he said. “You’ve really got to get your head around the fact that you’ve put yourself in a position to earn a better income, to have a better career.

“I don’t think it’s panic mode all of a sudden because you graduated six months ago and now you have to start making payment on your loans. That’s just part of growing up.”

Unlike Pereira, Abbott doesn’t believe paying off your loans immediately is always the best strategy. He stressed the need to come up with a comfortable repayment plan that leaves room for spending on “career preparedness” – things like new clothes for interviews, job board subscriptions and commuter vehicles.

He said that students need to be able to separate “good debt,” like student loans and mortgages, from the real killer: consumption debt. With today’s low interest rates, student loans rack up interest at around 5 per cent per year, and income tax credits mean the effective interest rate is even lower. Credit cards, meanwhile, run up rates anywhere from 18 to 25 per cent.

As much as possible, students should avoid graduating with an unpaid credit card balance, he said. “For the life of me, there’s no reason why anyone – especially a recent grad or new student – needs more than one credit card, two at the most.”

He added that the most important advice he can give students is to not dwell on school debt. “If you focus on getting the better job, on earning more money, the debt will take care of itself,” he said.

“Focus on where you want to go, rather than what you feel is holding you back.”